2. Trigonometric and hyperbolic functions #

2.1. Trigonometric functions #

Trigonometric functions associate the sides of a right angled triangle to its angles. The three basic trigonometry functions are:

cosine: ratio of adjacent to hypotenuse

sine: ratio of opposite to hypotenuse

tan: ratio of opposite to adjacent

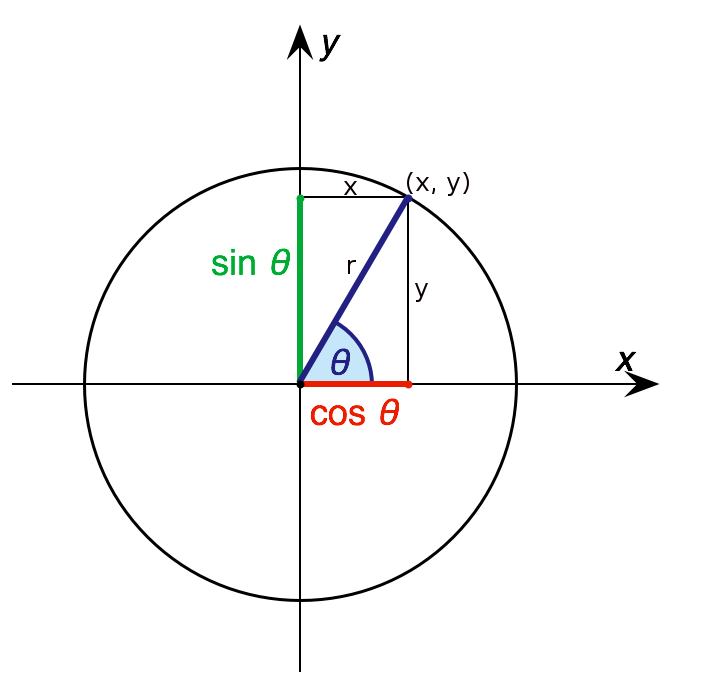

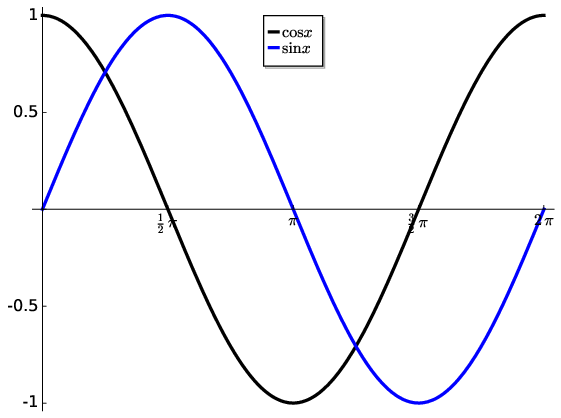

Since the input angle can be 0-360\(^{\circ}\), these trigonometric functions are typically defined using a circle. If the radius of the circle, i.e the hypotenuse, is set to 1 the sine and cosine ratios reduce to opposite and adjacent respectively. As the angle increases the values of these ratios change and repeat periodically for each cycle around the circle. Due to their periodic nature, trigonometric functions are used frequently in physics to describe oscillating phenomena.

Fig. 2.1 Trigonometric functions relate the ratio of two sides to an angle of a triangle.#

Fig. 2.2 Cosine and sine functions are shown for a single cycle for \(x=0\rightarrow2\pi\). Notice that the functions differ in phase by \(\pi/2\).#

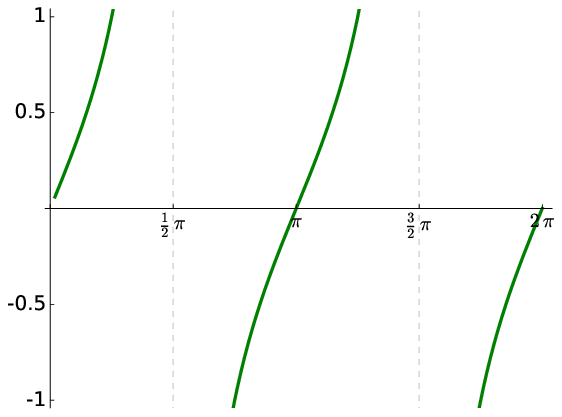

Fig. 2.3 The function \(y=\tan (x)\) is shown for a single cycle for \(x=0\rightarrow2\pi\). Notice the asymptotes at odd multiples of \(\pi/2\) .#

The other three possible ratios should also be noted:

2.2. Trigonometric identities #

There are many standard identities which can be useful in solving analytical problems in physics. Memory of these is of course not required but you should be aware of their existence or even better practice proving them!

The first set relate the squares of the functions and can be proven via Pythagoras’s Theorem:

The double angle formulae are:

The sum formulae are:

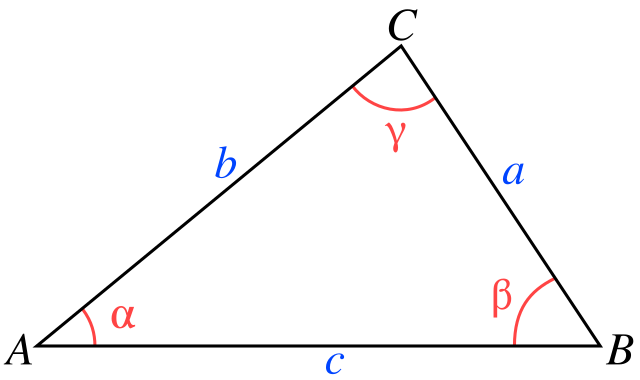

Finally there is the cosine rule:

the sine rule:

and the formula for the area of a triangle:

where a triangle has sides of length \(a\), \(b\), \(c\) and corresponding angles \(A\), \(B\) and \(C\), see Fig. 2.4

Fig. 2.4 Triangle with sides of length \(a\), \(b\), \(c\) and corresponding angles \(A\), \(B\) and \(C\).#

2.3. Hyperbolic functions #

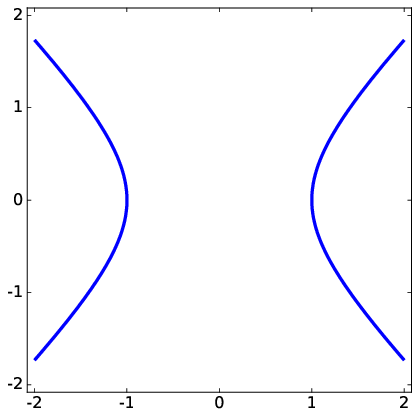

Whereas the standard trigonometric functions are based on circles (\(x^{2}+y^{2}=r^{2}\)), hyperbolic trigonometric functions are based on hyperbola (\(x^{2}-y^{2}=1\)) as shown in Fig. 2.5. The geometry defined by hyperbolic functions has numerous applications in physics.

Fig. 2.5 The hyperbola defined by the equation \(x^{2}-y^{2}=1\).#

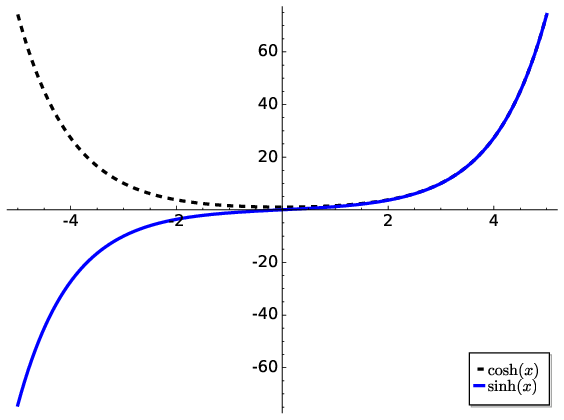

The functions themselves are combinations of exponential \(e^{x}\) curves and define hyperbolic versions of the trigonometric sine, cosine etc.:

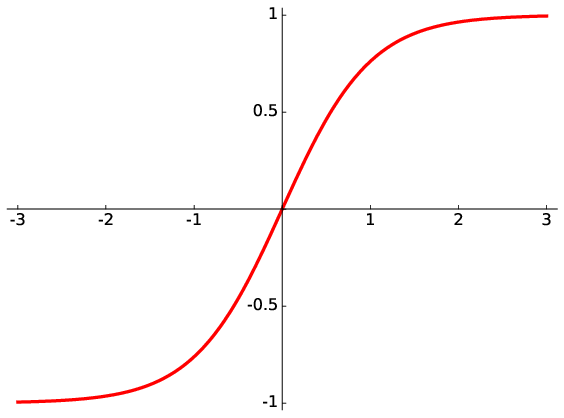

The graphs of these functions are shown in Fig. 2.6 and Fig. 2.7.

Fig. 2.6 The hyperbolic functions \(\sinh (x)\) and \(\cosh (x)\)#

Fig. 2.7 The hyperbolic function \(\tanh (x)\)#

There are also the corresponding reciprocals:

There are many identities involving hyperbolic functions, analogous to the identities for trigonometric functions. Some of the most useful are:

Can you spot a pattern relating trigonometric and hyperbolic identities?